It’s only really since the invention of ‘heritage’ that the act of preserving in aspic (or in the case of the National Trust, a nice artisan marmalade) our buildings of note, that the continual re-appropriation of components from building to building (of a particular age at least) has effectively stopped.

Some things are built to last; castles, the Pyramids at Giza, Stonehenge, to name but a few examples of long-lived built infrastructure. For most of our construction history however, the more prosaic or humble a structure may have been, the more likely it is to have been demolished, altered, moved or re-used in something else over the course of several iterations of use, build and ownership.

It’s only really since the invention of ‘heritage’ that the act of preserving in aspic (or in the case of the National Trust, a nice artisan marmalade) our buildings of note, that the continual re-appropriation of components from building to building (of a particular age at least) has effectively stopped.

From humble beginnings

Demountability has however, been a desirable attribute of the built environment over the ages too. The Normans – who upgraded their fortifications over time, started off with timber flat-pack Motte and Bailey palisades and ramparts, quick to erect and allowing the establishment of a foothold in a newly occupied land.

Nomadic peoples have long perfected the art of travelling with entire encampments, bundled and then re-built at each resting place over the course of many years, if something breaks it is replaced, thus the whole becomes an ever changing – yet always the same – concatenation of parts. The high watermark of this attitude of mind can be seen in Japan and the continual 20 year cycle of shrine (re)building, embodying the Shinto concept of wabi-sabi the idea of impermanence and imperfection, ‘nothing lasts, nothing is finished and nothing is perfect’.

To a sustainable future

In the modern age our concerns are less spiritual and more corporeal, concerned as we are with sustainability and material use in an era of impending resource scarcity and a growing realisation that we may have broken the planet’s thermostat.

An adaptable future

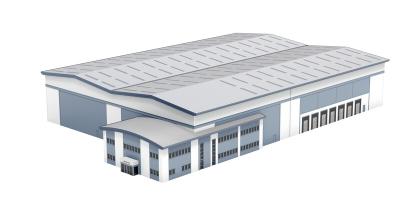

Demountability and re-use are important, desirable attributes of modern buildings and structures. The ability to de-construct and relocate, recycle or re-use parts, or whole structures opens up some interesting and challenging avenues of exploration for designers.

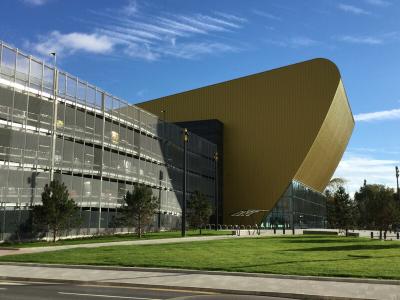

Firstly; there is the challenge of appropriate design. We can already point to examples of multi-application building typologies, with variations on the big shed being used for, warehousing, manufacturing, retail, education, sports, leisure and technology applications such as data centres. So the challenge here is to provide an aesthetic which does not tend towards a generic Goosewing Grey built environment redolent of out-of-town retail parks, but to try and inject some individuality and originality into something which is, intrinsically, the same.

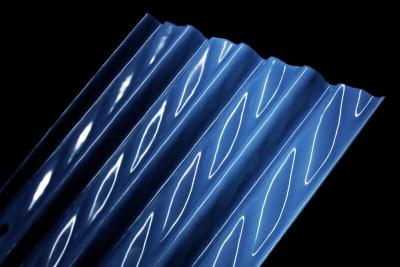

Secondly there is the spectre of ‘detail’. If building were to naturally evolve towards a mean multi use aesthetic, then any chance for an expression of quality might exist in the way components are designed to be joined (or taken apart) a new aesthetic might emerge of ‘small details’, or components might be made to have several lives across several different buildings, they might be ‘smart’ existing in a similar thought space as –say- a memory upgrade for a computer, or a faster processor.

Thirdly there is the economic challenge, Such a proposition must make sense financially. Why is it usually cheaper to buy a new washing machine when your old one breaks down? The infrastructure to support a refurbishment and re-use economy must be put in place alongside the new production route.

The realism

This can be easily imagined and in some small examples is already in-place for less smart components, such as a steel frame for example, properly catalogued and certified, could also be used time and again in different structures. Opportunities presented by BIM accompanied by the tagging of parts (using RFD chips for instance) would allow the use, position, age and even the loading of individual beams, columns and purlins etc. to be determined, their place in a new structure designed before the old one is dismantled. Buildings, in the words of someone much wiser than me, would become ‘warehouses of their own parts’.